Welcome to August!

As the leaves start to change color and the air gets a little cooler, you know that autumn is on its way. For some people, it is the best season of the year.

I know it’s definitely my favorite time of the year.

There’s something about the crisp, fresh air, the beautiful leaves, and new beginnings that feel nostalgic and cozy. I love the opportunity that the season brings to reconnect with myself and feel more in tune with nature and the world around me.

If you’re someone who loves summer and hates saying goodbye to the warm weather, transitioning to fall can be a challenge.

But it doesn’t have to be! There are plenty of simple ways to ease into the new season, ensuring that you make the most of the autumn months.

This edition of The Wellness News is about making the most out of the last month of Summer and preparing yourself for a wonderful, productive and healthy Fall.

Enjoy!

Chris

Table of Contents

Look what we have this month!

- Welcome to August

- Convention Product Releases

- 10 Simple Ways to Transition into Fall

- Canada Gifts with Purchase

- New Bundle Madness

- Transparency -- The New Seed to Seal Website

- August Recipe -

- US Gifts with Purchase

- EU/UK Gifts with Purchase

- Habit Stacking - How to make new habits easier

- Young Living Events and Promotions

- The Summer Night Sky - Why it is important to your Health

- Night Sky Diffuser Recipe

- New Perspective Oilers Education Series

- Coffee with Chris

- Join the New Perspective Oilers Facebook community

2023 Convention Product Release!

Mind Blown!

Some are available via the Canadian store, some are NFR and some were just available at convention....but what we know is that they are ALL Game Changers.

For more specifics on each product, check out our New Perspective Oilers FB Group for the details!

Immugummies, Daily Prebiotic Fiber and Green Omega 3 are all available via the NFR (US Store) -- Young Living charges the exact same price in US and Canadian so you AREN'T paying more by buying via US.

With Fall coming, these daily health habits will help you cruise by all the sniffles, coughs, and body aches that the first month of school brings!!

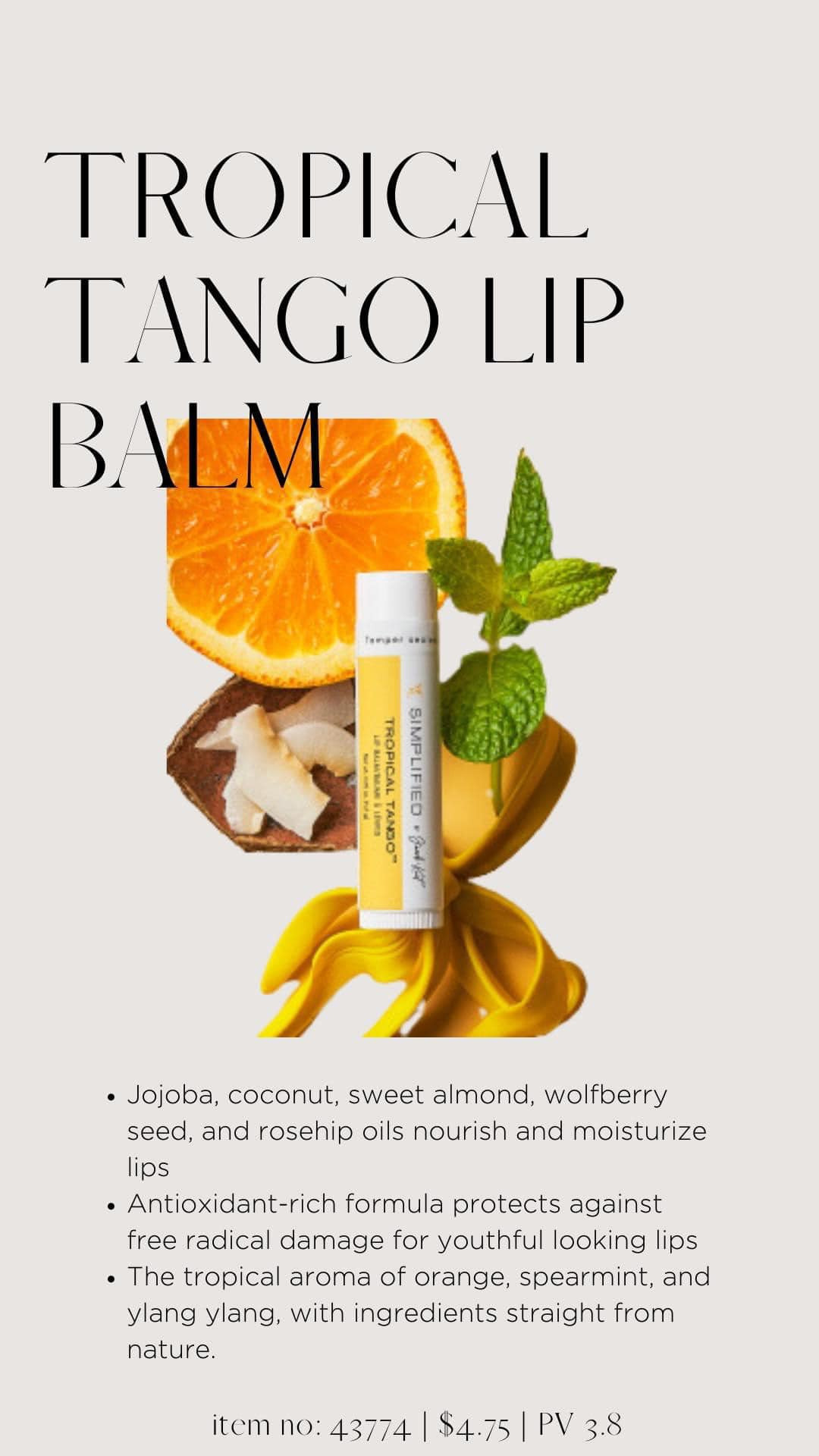

Your lips need support and protection whether it is from hot sunny dry days or cold brisk fall and winter weather.

You will fall in love with this dreamy tropical lip balm faster than a summer romance and longer than a winter blizzard!!

Gorgeous and silky, this hand cream will transport you to a tropical beach any time of year!!!

Available via the Canadian store, you will want one for your purse, your bathroom, and your bedside table. Would also make great stocking stuffers for those bleak cold months of winter!

Check these out AND MORE by cllicking below

Oils like the convention theme oil Ignite Your Journey and the original recipe Valor are also here!!! Get them while supplies last.

10 Simple Ways to Mindfully Transition from Summer to Fall

1. Journal for a Fresh Start

Fall marks a new beginning and a time for change. So, this is the perfect time to realign with your intentions for the year.

It’s also a good time to look back and reflect on your summer and write about all your memories so you can mindfully close that chapter and focus on the present moment.

These journal prompts for a fresh start will help you get realigned for the Fall season.

2. Create a Fall Bucket List

What would make you happy, help you become your best self, and make the most of what the fall season has to offer?

Create a Fall bucket list of all the seasonal activities you want to take part in this time of the year.

You can add activities like apple picking, fall baking, cozying up with a warm drink, and more. Check out this ultimate Fall bucket list to give you some ideas.

3. Make a Fall Vision Board

Who says you have to create a vision board once a year? I enjoy creating a new vision board every season where I put my intentions and goals for that season. I like to look at it every day so I can really envision what I want a particular season to look like.

You can also bring your Fall bucket list to life with images.

You can also bring your Fall bucket list to life with images.

4. Organize and Refresh Your Space

Take some time to declutter and organize your home and your life. Get rid of anything that you no longer need or store the summer supplies that you are no longer using.

Then, refresh your space for Fall with the Simplified Fall series by Jakob and Kate, Fall decor, cozy blankets, and whatever else gives you those fall vibes.

Then, refresh your space for Fall with the Simplified Fall series by Jakob and Kate, Fall decor, cozy blankets, and whatever else gives you those fall vibes.

5. Find Your New Routine

Our daily routines tend to shift with the seasons.

Your daily routine can include things like the way you spend your morning routine, your sleep schedule, and seasonal hobbies.

It’s important to find a fall routine that works for you, your responsibilities, and your schedule.

6. Shift to Different Foods

During the summer you might be eating colder foods like salads and fruit. But, on cooler days you will probably find your body wanting to be nourished with warm grounding foods.

You might be craving more soups, teas, and spices like cinnamon. Try some Thieves oil or switch to Thieves Household cleaner to get those gorgeous Fall smells throughout your home.

Seasonal food is fresher, tastier, and more nutritious than food consumed out of season.

In-season fresh fall foods include things like pumpkin, squash, pears, and apples.

In-season fresh fall foods include things like pumpkin, squash, pears, and apples.

A seasonal food guide is a great way to see what is in season in your geographical area.

You can create a meal plan and try out new whole-food fall recipes to keep you healthy and balanced during the cooler fall months.

7. Try New Movements + Exercises

Daily movement is important for your mind, body, & soul.

The fall time is the perfect time to start a new workout routine or even enjoy the outdoors before it gets too cold.

The fall time is the perfect time to start a new workout routine or even enjoy the outdoors before it gets too cold.

You can go for a hike and enjoy the beautiful leaves, go apple picking, practice yoga, or just take a walk in the park.

Find exercises that work for you and your body and before starting a new workout consult your doctor if you have any chronic health conditions.

8. Change Your Sleep Schedule

Days are getting shorter so you will probably have to adjust your sleep schedule.

During the summer you may have been going to bed late because in some places the sun doesn’t go down till after 9 PM.

During the summer you may have been going to bed late because in some places the sun doesn’t go down till after 9 PM.

But, since it will be getting darker earlier you may need to change your sleep times and go to bed earlier since your circadian rhythm will be disrupted.

After several days, as you fall asleep earlier and wake up earlier your circadian rhythms will eventually adjust to the new schedule.

After several days, as you fall asleep earlier and wake up earlier your circadian rhythms will eventually adjust to the new schedule.

9. Create a Seasonal Playlist

Listen to the perfect tunes to get yourself into the fall spirit.

You can create your own seasonal playlist or check out these fall playlists that are all about the fall vibes.

10. Embrace Change

A new season is out of your control so why not just embrace it?

Even if you don’t like the Fall Season (for some crazy reason) you can’t change it so focus on the things you can control.

Even if you don’t like the Fall Season (for some crazy reason) you can’t change it so focus on the things you can control.

Embrace the change in the weather, the change in the leaves, and the change in your routine.

Final Thoughts

The fall season is a time of rejuvenation, relaxation, and letting go. Always remember to create fall rituals and routines that feel good to you.

With these tips in mind, I hope that are able to transition from summer to fall and enjoy the fall season to the fullest.

Carve out moments of calm and treat yourself to soothing scents, bath bombs and a hydrating balm in August gift with purchase.

These self-care goodies will help you make space for relaxing routines, so you can welcome autumn with a renewed sense of mind.

NEW BUNDLE MADNESS

That is why YL has announced several new options for us all.

This Summer Fresh Starter bundle features the gorgeous Macaron diffuser -- ceramic top which will look great no matter where you put it -- and a selection of key oils to try. Add to that some lip balm, the luxurious coconut lime body balm and you have a real winner!

Check it out Summer Fresh Right Here!

Make A Shift: Daily Wellness Kit

Maybe you hesitate to try yet another health "fad". Or maybe you have tried others in the past and haven't seen results. And possibly, you have tried something else and haven't followed through and now feel bad about yourself.

Well there is NEVER a bad time to try again -- to try to improve your health.

And Ningxia has been here waiting for you!

Scientific research shows an improvement in energy, sleep and reduction in food cravings so what could be better to start? This is MY go to daily NON-NEGOTIABLE supplement and I feel the difference.

Now YL makes it even easier for you to start!

Support health and wellness deliciously with this value-packed kit.*

The Make a Shift™ Daily Wellness™ Kit includes:

- NingXia Red Singles, 30 ct.

- NingXia Nitro tubes, 14 ct.

- Orange Vitality essential oil

- Lime Vitality essential oil

Make A Shift: Essential Solutions Kit (via NFR)

Experience a world without compromise. Inside this Young Living® kit, you’ll find everything you need to guide you and your family as you make the shift to a happy, healthy lifestyle.

The Make a Shift™ Essential Solutions™ Kit includes:

The Make a Shift™ Essential Solutions™ Kit includes:

- Thieves® essential oil blend, 5 m

- Purification® essential oil blend, 5 ml

- Lavender essential oil, 5 ml

- Peppermint essential oil, 5 ml

- Deep Relief™ Roll-On, 10 ml

- Stress Away™ Roll-On, 10 ml

- FreshStart™ Diffuser (exclusive to this kit!)

AND such a goregous new diffuser!!!

Make A Shift: Healthy Home Bundle

Say goodbye to harsh cleaning chemicals and hello to a plant-powered clean!

The Make a Shift™ Happy, Healthy Home™ Kit includes:

The Make a Shift™ Happy, Healthy Home™ Kit includes:

- Thieves® essential oil blend, 15 ml

- Lemon essential oil, 15 ml

- Thieves Household Cleaner 14.4 oz.

- Amber Spray Bottle

- Thieves Laundry Soap

- Thieves Kitchen & Bath Scrub

- Thieves Dish Soap, 12 oz.

Available via the US Store (NFR) this kit is the essentials you need to ditch the toxins and get a healthy clean! Sooo critical for Back to School and Back to Work time of year!

No Greenwashing Here!

Just Transparency

SEED TO SEAL, SCIENCE, & FARMS

THIS is what made Young Living so attractive to me above and beyond their products!

1. Our Seed to Seal website has been refreshed & revamped: www.seedtoseal.com

2. We now have Certificates of Analysis (COA) and testing results for our essential oils available online! Visit the digital library to search by single oil or lot number: https://library.youngliving.com/en/us/?categories=Testing

3. Slave-Free Alliance (SFA) - an organization that helps businesses protect their operations, supply chains and people from modern slavery and labour exploitation. YL has always had this as a forefront in their mission and practices but has officially become part of SFA.

4. YL has partnered with Route for package tracking so customers will have visibility of order tracking from order confirmation to delivery at their doorstep! Total order transparency

August's Featured Recipe

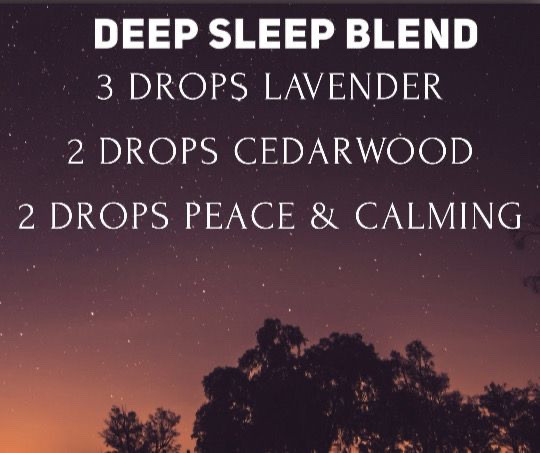

Deep Sleep Blend

With all the effort of packing each summer's day with as much as possible, sometimes getting a good deep sleep can be illusive.

Whether you are planning for a trip, heading out to the cottage or just staying at home, our minds can race with all of our to-do list items and keep sleep at bay.

Try this gorgeous diffuser blend and finally get that deep sleep you need to tackle every single day with energy and enthusiam.

August's US Gifts with Purchase

Wrap up your summer by unlocking the secrets of gut health! Treat yourself to our free gifts with purchase, including our spicy Ginger Vitality™ and zesty Lemon essential oil. Promote healthy digestion with the 17 billion live cultures in our Life 9® probiotic supplement.*

To make your wellness journey even more extraordinary, you can also pack along a mini travel supplement case to carry your MultiGreens™ capsules. As always, you’ll also receive 10 loyalty points with a loyalty order of 100 PV.

Mini Supplement Travel Case

Make this August extraordinary! Get ready to elevate your summer experience with our incredible PV Promo! Indulge in the refreshing aroma of Eucalyptus Radiata, pamper your skin with the luxurious Mirah Luminous Cleansing Oil, and enjoy the wonderful scent of Vanilla.

We're also thrilled to introduce two fantastic new additions: Seaside and Tropical Tango essential oil blends from the Simplified by Jacob & Kait Summer Collection.

Transform your space into a beachside sanctuary with Seaside and let the bright and uplifting aroma of Tropical Tango transport you to a tropical oasis.

How Habit Stacking Can Help You Have the Best Fall Ever

Forming bad habits is easy, but building good habits is surprisingly hard—even though most of us crave routine to one degree or another. Luckily, here’s a way to use your natural inclination toward routine to build and maintain a new habit. It’s called habit stacking, and you can think of it like glueing a new habit to an existing one.

What is habit stacking?

Habit stacking happens when you tack a desired behavioral change onto an existing routine. Theoretically, that way the thing you’re having trouble sticking with just becomes part of your broader, ongoing string of habits. Consider the things you already do every day: Brushing your teeth in the morning and at night, making your coffee in the morning, walking your dog at lunchtime, etc. During any one of those, you can add in a second necessary task that will benefit reciprocally from happening alongside your existing routine.

This concept was popularized in 2017 by S.J. Scott, who wrote Habit Stacking: 127 Small Changes to Improve Your Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Since then, it’s blown up, with other psychologists adding their own support for the practice. Science agrees: Building routines is key to overall health and wellbeing, and our brains are wired to seek out routines. Once you have one habit neurologically wired in, building others around it is much easier.

How to get started with habit stacking

There are plenty of ways to build a habit stack, but first you need to identify the tasks you’re struggling with. For example, if you know you need to sort through your emails every morning but you tend to put it off as soon as you log in to work, keep it in mind as a possible candidate for adding to a stack.

Once you’ve identified the things you want to do but don’t, identify the things you do do, whether it’s taking a break every day at 3 p.m. to scroll social media or doing the dishes after every meal. Examine each and look for ways you could stack the less-sticky tasks on top of them. If you forget to call your mom often, stack that on top of doing the dishes. If you need to sort your email inbox, do it while you drink your morning coffee.

The trick is to figure out which things can stack cohesively. You can’t return phone calls while you’re running at the gym, but maybe you can do so while you’re commuting. You can’t study while you brush your teeth, but you can practice your deep breathing.

Once you’ve determined which habits can stack, write down your plans somewhere like a Google doc—”I will respond to my emails every morning by 10, while I eat breakfast”—and for the first few days, actively check in on it to make sure you’re staying on top of them. Eventually, they’ll become habitual, just like the activities you’ve paired them with

Fire in my belly

Fire in my belly

Ok friends, winning a year's supply of Ningxia Red in the Kona challenge got me fired up!

I mean I just won a year's supply of Ningxia Red AND six amazing oils with a beautiful bamboo case just for working MY business MY way

It showed me that it IS possible for someone in YL with a small business to compete with the big kids on the block and win!

So what does YL do after Kona challenge is over?

Do they say "ok that is it for this year?"

Nope -- THEY DOUBLE DOWN ON THE WINNING

Everyone meet the Ready to Grow: Dominican Republic challenge.

This challenge is different though!!! It is ONLY for people whose businesses are at the first 6 levels of their YL journey -- so YOU AND ME, friend!

So whether you have been thinking about earning some extra cash, or getting the products you want for free, or replacing your current stress-filled income with your own efforts -- then THIS is YOUR challenge.

Join me and let's go for this together!!! I will be having an in-person business event July 31 aqt 6pm at my home OR stay tuned for some online opportunity events coming soon.

This is the moment you have been waiting for -- don't put your dreams off for another year.

PM me TODAY and let's get you started on earning this trip!!!

Canada & USA!!

Earn rewards for growing your business with our biggest and best sales incentive yet.

Each month, when you sell 100+ PV to two new enrolling Customers and/or Brand Partners through a qualifying monthly (ER) order, you’ll get an additional exclusive reward beyond the Young Living Sales Compensation Plan.

Keep up your momentum and you’ll be eligible for extra rewards after two, four and six consecutive months, with a grand total of nine amazing rewards to look forward to!

Monthly rewards

Share Young Living with two of your friends and family in July! When they place their first-time order on Essential Rewards with 100+ PV, you’ll earn a free Stanley 40-ounce Adventure Quencher.

Retail value: $77.40

Share Young Living with two of your friends and family members in August. When they place their first-time order on Essential Rewards with 100+ PV, you’ll earn an exclusive Young Living diffuser.

Retail value: $126.25

Coming soon! Check back on September 1 for reward details.

Coming soon! Check back on October 1 for reward details.

Coming soon! Check back on November 1 for reward details.

Coming soon! Check back on December 1 for reward details.

.

.

Share Young Living with two of your friends and family members for TWO consecutive months with qualifying orders and get a Saranoni blanket.

Retail value: $192.20

Coming soon! Check back later for reward details.

Coming soon! Check back later for reward details.

How to receive your reward

Place a monthly (ER) order of at least 50 PV within 90 days of the commission run. Your earned reward will be included automatically in this product order.

The 90 days will start over for each month. For example, if you qualify for a reward in July, you’ll have 90 days from the August commission run to place a monthly (ER) product order and have your reward shipped with it.

PM me for more information or if you have any questions!!

UNBELIEVABLE

Just when you thought the incentives were all out there -- this new one just announced!

I would LOVE to see this farm!

Earn a trip to Ecuador!

We’ll select 48 qualifiers from around the world:

- 30 qualifiers from the U.S./Canada

- 10 qualifiers from APAC

- 6 qualifiers from EMEA

- 2 qualifiers from LATAM

*More details , and FAQs coming soon !

Summer Nights

Add some Night Sky to your Wellness regime

By Robert Dick, Harrowsmith Magazine

The night sky doesn’t change very much, or so we are told. Aristotle (384–322 BC) set the stage for this assumption with his philosophy of the unchanging starry realm. His teachings persisted for almost 2,000 years. After it was adopted by religion, to question it was heresy. Observers of the night sky slowly chipped away at these teachings by witnessing changes in the night sky. Eventually, these observations could no longer be ignored. The night sky does change, although slowly.

To be fair, changes in the universe occur very slowly, spanning millions of human lifetimes. Some stars have lived as long as the human species, and others have been around for billions of years. Closer to home and with greater rapidity, the planets orbit the sun, and the rotation of Earth ushers the celestial objects across our sky every night.

You might think that one clear dark night is as good as the next, but I don’t think so.

Consider a walk in a park, a symphony or the theatre. Our experience will be different with each exposure. Our awareness and imagination is different every day. Our memory is as much about what we bring to the experience as the event itself.

The presentation of a play is organic—it changes with every performance. During a walkabout, the smell of the air, the sun’s heat and the passersby can never be repeated exactly the same. The flavours of good food vary with the spices and preparation. And as we get older, our aches and pains seem more dominant. Real life is not boring!

We experience a summer’s night. There are many distractions during the day. Each one is like a different spice that alters our experience, but at night, the visual landscape is subdued, distractions are muted or hidden, and our other senses are magnified.

The late-evening dew after a hot, dry day intensifies the scent of the soil, grass, flowers and trees. Without the sound of traffic, our hearing is focused on the sounds of crickets and frogs. More subtle than those sounds are the leaves rustled by a breeze, and the “sigh” that’s produced when the wind blows through needle clusters of pine trees. Most birds are quiet after dark, but there are a few nocturnal species that call out around wetlands and lakes.

Night is an environment and ecosystem, and all our senses combine to create a memorable experience. Not the least of which is our sensitive night vision, which reveals the stars, completing the memory of night.

None of these stimuli are repeated quite the same. Every night creates a new memory, and missing any one of these stimuli weakens the experience.

Photographic images can’t do it justice, even though the stars dominate our vision. The light level is low, which “removes the colours from our sight” (so sang the Moody Blues in “Nights in White Satin” in 1967). And there is a visual texture to the sky—it looks “grainy” because of the reduced visual acuity of our night vision.

During an early-summer evening, the hazy band of the Milky Way rises like a fog bank above the eastern horizon. In late summer, it has rotated across the sky, such that it stands almost vertically above the southwestern horizon.

You and your children may not experience the night as we have in the past. Our ability to see the night sky is changing at an accelerating rate. Look at the first image in this essay. Lights now line the shoreline, and the light from hamlets, towns and cities causes the sky to glow. Most of this light is not natural and, sadly, most of this light is not necessary.

Outdoor lighting has been increasing by 2.2 percent per year—much faster than the population growth. Why is this getting worse? We should be saving energy, not using more of it.

Using more energy-efficient lighting has led to the installation of more and brighter light fixtures, increasing the use of energy for all-night lighting. Lights are now being installed where previously we did not think they were necessary. Also, the emitted white light blinds our night vision and overwhelms the natural night. The light fixtures create a small illuminated patch at the expense of seeing the distant treeline, which provides our peace of mind with a “sense of place” and has taken the night sky from our children.

Fifty years ago, you could see the Milky Way from the suburbs of major cities, but now that is virtually impossible. More importantly, the loss of darkness and the stars at night impacts our physical and mental health. Artificial light at night changes our body’s natural mechanisms to fight disease, including cancer.

How could we let this happen? Only in the last 20 years has outdoor lighting become so bright that these issues have become obvious to medical researchers and philosophers. The night sky becomes featureless and no longer worthy of our attention. As we lose the experience of nature, we lose our perceived connection to it.

There is hope on the horizon. It begins with national and international programs to “protect the night” and the 60 percent of all life that depends on it.

We have Dark-Sky Preserves. Public and commercial parks and even municipalities that want to reduce their impact on the environment can work toward achieving this designation by limiting the amount of light pollution they emit. Technology is making this much easier, but applicants must still make the effort to use light carefully.

The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (RASC) manages the Canadian program that recognizes the protection of large rural areas and even large urban parks. The critical requirement is the Canadian Guidelines for Outdoor Lighting (CGOL, pronounced “seagull”), which is available, along with the application requirements, on the RASC website (rasc.ca/dark-sky-site-guidelines). These are the only lighting guidelines based on human vision and the sensitivity of wildlife to artificial light.

The International Dark Sky Association in Tucson, Arizona, has its own program (darksky.org/our-work/conservation/idsp/become-a-dark-sky-place). The association’s outdoor lighting requirement is not as eco-centric, but it will designate sites around the world.

However, these programs recognize protected areas, whereas wildlife do not stay within our surveyed boundaries. We have the ability and technology to cut light pollution at the source by using lighting with low ecological impact. These products have been developed in Canada, and now other manufacturers are beginning to copy the technologies.

How can your town get on board? The scientific research has defined the course with the following four easily achieved principles.

- Do shield light fixtures so that no light shines beyond your property. This cuts glare and light trespass and reduces the amount of energy you use for lighting.

- Do not use white light. The blue colour that makes it look white amplifies the sensation of glare, and is the most bio-disruptive light we produce. We can use shielded low-power “bug lights” around your home, and municipalities should use fully shielded amber LED street lights.

- Do not over-light. The lighting industry recommends a reasonable light level on residential streets. Do not exceed them. With shielded amber lights, we can see better with less.

- Schedule the light based on need. Rush hour is typically over by 10 p.m., so lighting levels for peak traffic can be dimmed for most of the night.

Some local governments have developed or are considering developing policies that illuminate their town to many times the industry safety levels, but there are consequences. Over-lighting creates distraction and glare, which slows reaction times and undermines visibility, safety and security, and the higher cost is carried by all taxpayers—not just the city officials or politicians who make these decisions.

Now that we know what we are losing and that there are solutions, we need to reduce the use of white light and unshielded fixtures.

Your neighbours won’t do it unless you ask, and cities won’t do it unless you demand it of your elected officials.

Night Sky Diffuser Blend

Take some time to lie out in the yard and look up. Take pillows and blankets so you are comfortable and can stay awhile.

The vastness of just our own galaxy is enough to balance your nervous system and bring you into harmony with our planet.

Try to stay out as long as possible so you experience the slow turning of our world and the ever changing views above us.

For the Summer months, most our education shifts to in group series -- FB classes that pick a topic and have several posts on it over a couple hours.

For the Summer months, most our education shifts to in group series -- FB classes that pick a topic and have several posts on it over a couple hours.

Zoom Link for All Classes not hosted in the Facebook community is below

Join the New Perspective Oilers Facebook Community

August's Education Opportunities

Check out the Events tab for more information or, better yet, change your notification settings to ALL for New Perspective Oilers so you don't miss a single one!!

Invite a friend. Invite a family member. Invite anyone you know who could use a community of wellness seekers.

And don't forget - many of our Zoom classes are posted on the Youtube channel so you can watch and rewatch!

COFFEE WITH CHRIS

For the Summer months, Coffee with Christ will only be on SELECT Saturdays .

Saturdays n May for a live and interactive virtual coffee shop gathering. This Zoom and FB Live event is just a way to connect and chat on a casual and friendly basis - no plan, no agenda, just coffee and conversation. Let's catch up on life and have a laugh together.

So grab your cuppa whatever you want and find your way to our table for some fun!

Join the New Perspective Oilers Facebook Community

This happy group of people are all here to work on our wellness, with the help of some terrific Young Living Products. Join the group to be first in the know about new education opportunities, new product launches, and some pretty fabulous draws!

Well that's it for February! Stay on top of ALL the news and supports by checking in at New Perspective Oilers FB Community OR New Wellness Perspective website.

Take some time in August for some serious self-care. We all know that September is a month filled with routines and schedules -- get your mind and body as prepared as possible for a successful healthy Fall.

As always if you have any comments or concerns pop me an email at hello@newwellnessperspective.com